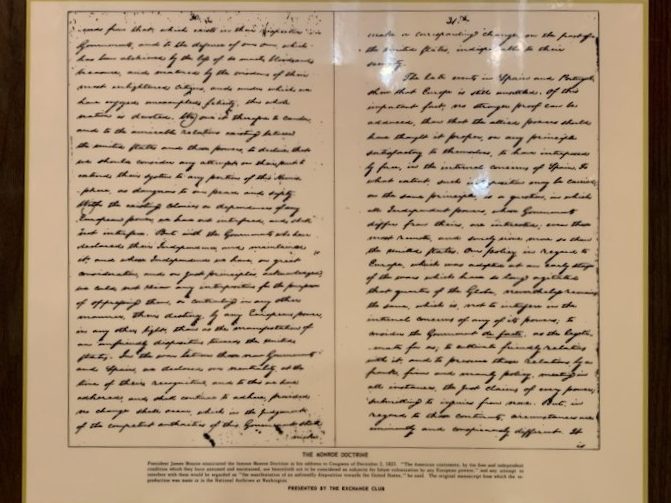

Excerpt From the Monroe Doctrine

This unassuming copy of one of the pages in President Monroe’s 1823 address to Congress laid the foundation of what would be known as the Monroe Doctrine – one of the most influential parts of United States foreign policy for 200 years.

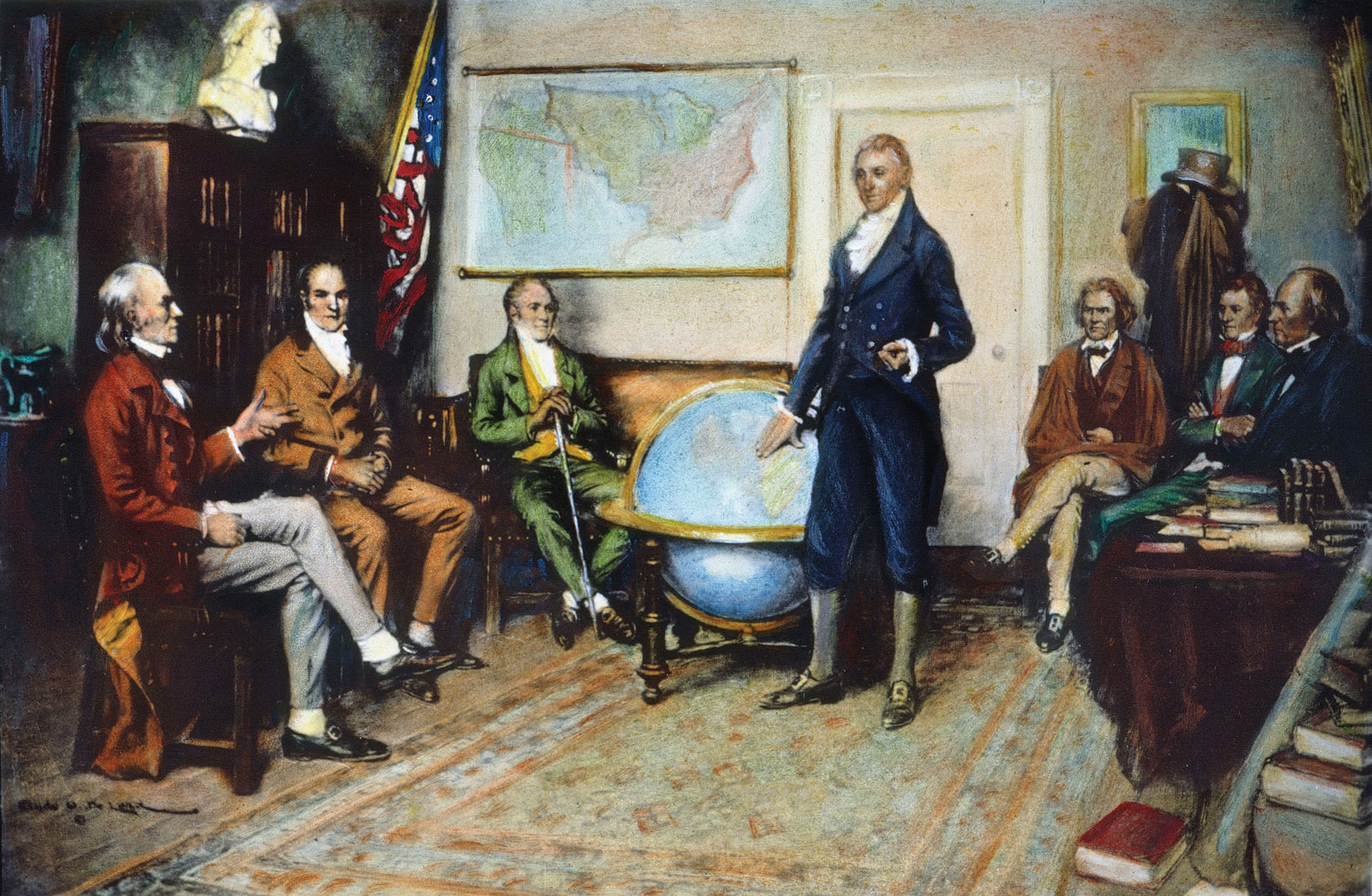

The Issuing of the Monroe Doctrine

In the 1820s, the United States stood on uncertain ground. It was confident after holding its own in the War of 1812 but was feeling threatened by the possibility of European colonization efforts in the Americas. Fears over the possibility of Spain forcibly reconquering the newly independent republics in South and Central America were high. The British were similarly worried and approached the United States about a joint statement on the matter. Despite some senior cabinet members supporting the bilateral statement, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams convinced President Monroe to issue just one statement from just the United States, to convey an independence of foreign policy.

In his December 2, 1823, address to Congress, President Monroe announced that protecting the Western Hemisphere was the responsibility of the United States, and it would not tolerate any further European colonization or interference in the Americas. The address also stated that the United States would remain uninvolved in European affairs. Copies of the address were given to Congressmen, and foreign diplomats wrote home to their governments about the new U.S. policy. However, the target of the statement was mostly the American public, who embraced it as a sign of American strength, action, and independence. Little did they know, the Monroe Doctrine would go on to inspire nearly 200 years of U.S. foreign policy.

Using the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine, combined with the idea that America was ordained to expand across the continent, would lead to the concept of Manifest Destiny, directly resulting in the growth of the United States to the Pacific Ocean and into the southwest. In the first decades that the Monroe Doctrine was in effect, it was the British who prevented European expansion in the Americas. With a vested interest in a free South America, the British used their powerful navy and diplomatic presence to prevent European meddling in the affairs of the Americas.

During the Civil War, the Monroe Doctrine briefly lapsed as the government became too concerned with the war to prevent European incursions. As such, in 1862, France and Austria invaded Mexico and installed a friendly emperor to rule – an action that the United States did little to counter other than voice displeasure. However, upon the conclusion of the Civil War, the United States took a more active role, pressuring Austria into not sending reinforcements.

With the completion of the Civil War, the United States was more powerful, and resumed its role in the enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine, such as in 1899 when it arbitrated a border conflict between Venezuela and the British colony of Guiana. This signified a more aggressive enforcement of US hegemony over the Americas, something that would be reinforced with the 1904 Roosevelt Corollary – which proclaimed that the United States had a “international police power” to end unrest in the Western Hemisphere. This policy would justify 30 years of military and diplomatic interventions in Latin America. While the right to intervention was renounced by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1934, the Cold War saw frequent covert intervention in South and Central America, with the government backing various dictators and anti-communist rebellions.

The Monroe Doctrine would also be symbolically invoked in 1962 with the Cuban Missile Crisis. President Kennedy declared that any attack by the Soviet Union on any nation in the Western Hemisphere would count as an attack on the United States, echoing the rhetoric of the Monroe Doctrine. Further, the United States used military and diplomatic pressure to make the Soviets remove their nuclear weapons from Cuba.

The Monroe Doctrine, although originally more theatrics than official policy, inspired and guided the foreign policy of the US for two centuries, making it one of the most influential decisions in our nation’s history.